The wonderfully weird world of mollusks

Discover these fascinating invertebrates in Utah and beyond!

By Kate Holcomb

DWR Native Aquatics Biologist

Statewide Mollusk Specialist

Have you ever heard of animals named creeping ancylid, sub-globose snake pyrg, button sprite or the sluice snaggletooth? What about the fatmucket, narrow pigtoe or gumboot chiton (aka wandering meatloaf)?

These are all mollusks. And yes, most mollusks have highly amusing names. The first list of names includes just a few of the many native snails found in Utah. The fatmucket and narrow pigtoe are freshwater mussels found in rivers of the eastern United States, and the wandering meatloaf is a kind of chiton (a class of marine mollusks) found in the northern Pacific Ocean.

Fatmuckets collected during a stream survey in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (left) and four narrow pigtoes (right) from a stream in northwest Florida.

The vast diversity of marvelous mollusks

So, what exactly is a mollusk? Elementary school science lessons might be a fuzzy memory for some of us, so here's a quick refresher: mollusks are invertebrates (they lack a backbone) and they make up the second largest group of animals after arthropods (the group of invertebrates that includes insects). There are approximately 85,000 identified species of mollusks alive today, but there are many new species being discovered all the time.

It's difficult to say what a typical mollusk looks like because this group of animals is so diverse. Commonly known mollusks include clams, octopi, squids, snails and slugs. Mollusks can be found in marine, freshwater and terrestrial (living predominantly or entirely on land) environments.

Along with their weird names, mollusks are also weirdly and wonderfully interesting animals. Many people have gone beachcombing at the ocean and are familiar with the wide variety of shapes, sizes, colors and textures of mollusk shells — the "bones" of dead mollusks — but fewer people have had the opportunity to explore the world of living mollusks.

The oceans are full of fascinating mollusks. Search online for "nudibranchs" and you will quickly see what I mean! Nudibranchs (a type of sea slug) have no shell for protection, but they use striking colors, patterns and body projections to send a message to predators that they are not worth eating.

Another group of sea slugs, the sacoglossans (solar-powered sea slugs), are able to produce their own energy like plants. Sacoglossans do this by eating algae and keeping chloroplasts (plant cells that photosynthesize) in their body, and it's very rare for animals to be able to do this. Cephalopods — octopus, cuttlefish and squid — are among the most intelligent invertebrates on Earth. If you have seen the movie "My Octopus Teacher," you are likely familiar with how smart they are.

And the gumboot chiton is just plain weird, but it is playing an important role in the field of biomimetics. (That's the science of mimicking nature to develop new technologies, such as how the tiny hooks on plant burs — the plant seeds that stick to your socks — inspired the invention of Velcro.) Scientists have been studying the chemical makeup of the gumboot chiton's teeth to help design robot parts that are hard and strong in some places and soft and flexible in others.

Taking a closer look at Utah's amazing mollusks

Despite being one of the driest states in the nation, Utah is home to a surprising diversity of mollusks. We have two native freshwater mussel species, 13 pea clam species, 57 aquatic snail species and 61 terrestrial snail species. The freshwater mussels and many of the snails can be found in surrounding states as well. However, some of our springsnails (tiny snails that tend to live in springs) are only found in one spring in Utah and nowhere else in the world.

Can you find the five small springsnails on the rock in the center of the photograph? These springsnails were found at the Fish Springs National Wildlife Refuge.

Our Utah mollusks may not be as showy as their marine relatives, but they are an important part of healthy ecosystems (unlike invasive quagga mussels and Asian clams).

Utah's mollusks are like nature's janitors and help keep the environment clean. Freshwater mussels suck water in through their siphons and filter the water through their gills to collect tiny food particles and bacteria. This filtering process helps keep the water clean and clear for us and other animals.

Snails in aquatic and terrestrial environments eat living and dead plant material and help prevent excessive vegetative build up. Snails and freshwater mussels also aid nutrient cycling in the environment and are an important food source for many animals.

If I have not already grabbed your attention, I will leave you with an introduction to the intriguing life cycle of the freshwater mussel. This animal's unusual adaptation is what got me hooked on mollusks when I was in college, and I have been fascinated ever since.

A mountainsnail feeding after a light rain. Kate found this mountainsnail in Millcreek Canyon near Salt Lake City, UT.

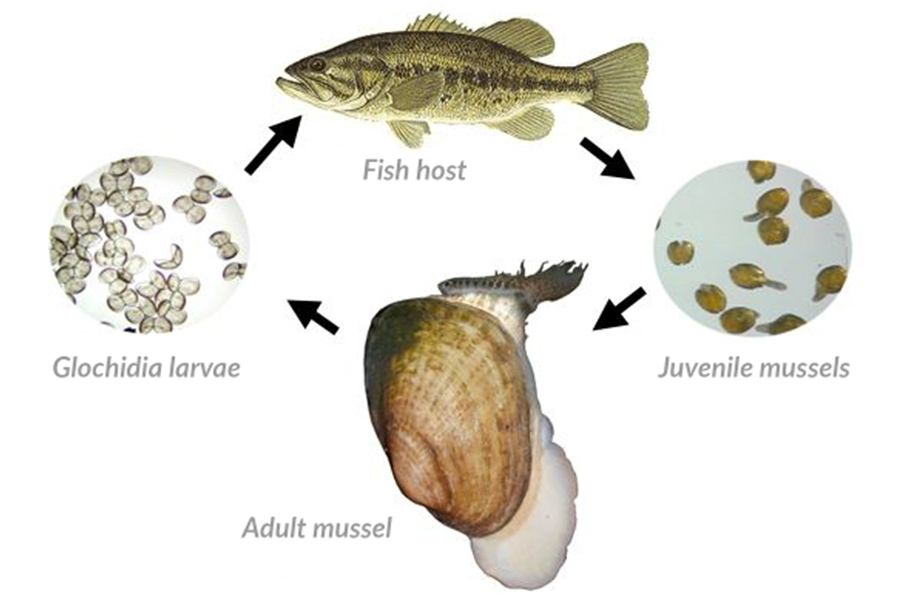

Freshwater mussels are unique in that they require a host fish to complete their life cycle. The life cycle begins when the male and female mussels spawn, and then the female mussel broods fertilized eggs in her marsupial gills.

While the eggs mature into larval mussels (called glochidia) in the safety of their mother's gills, the mother mussel is devising a strategy to attract the right host fish. Some mussels can only use certain fish hosts — not just any fish will do. If a mussel species uses a predatory fish as a host (like a bass), the female mussels will often make a lure from their own flesh that imitates the color patterns and movements of a prey fish.

When a predatory fish is fooled by a mother mussel's lure and tries to eat it, the mussel releases her glochidia toward the fish so that the glochidia can attach to the fish's gills. If the glochidia reach the gills of the appropriate host fish, they will hook on to the gills for a few weeks and use the nutrients from the fish's gills to grow and metamorphose into a juvenile mussel.

This process is not intended to harm the host fish — the glochidia need their host to be healthy if they are to survive! Once a glochidia has metamorphosed into a juvenile mussel, it drops off the fish, settles into the sand at the bottom of a lake or stream and begins its life as a freshwater mussel. Check out this video to see how this fascinating process works.

The freshwater mussel life cycle.

Photo Credit: Chris Barnhart and Joe Tomelleri, Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society

Some details about the life cycle of our freshwater mussels in Utah are still not fully understood. The winged floater likely uses a wide range of fish species as hosts. Floaters broadcast their glochidia in the water, and the glochidia's hooks and sticky threads help them successfully attach to a host fish (see this cool video for an example of what this looks like).

Check out this amazing video shared by DWR biologists! A speckled dace (a Utah native fish) tries to eat a conglutinate from a western pearlshell in a Utah stream.

Western pearlshells from other nearby states use salmon and trout as host fish, and they use conglutinates (tiny packages of glochidia) to transfer glochidia to the host fish. Mussels often create conglutinates that mimic a fish food item — like an aquatic insect — so fish will try to eat the conglutinate. As soon as the conglutinate is in a fish's mouth, it will explode like a bomb, and the glochidia will then have easy access to the fish's gills.

The freshwater mussel life cycle is weird, yet truly amazing. How do freshwater mussels make lures that are so lifelike and effective? They do not have eyes or a brain, so lots of time and trial and error have helped freshwater mussels hone in on creating the perfect lures. I encourage you to take some time to nerd out on freshwater mussel lure videos online — I bet you can't watch just one video!