Drought and our deer herds

How drought affects mule deer and what we're doing to help

Covy Jones

DWR Big Game Coordinator

As a wildlife manager, there are few natural disasters as frustrating as drought. It's not like a tornado, flood or blizzard — all isolated, short-term events with a limited range. Drought has been an ongoing event that's unfolded over multiple years across the West, and we've seen some of the worst of it here in Utah.

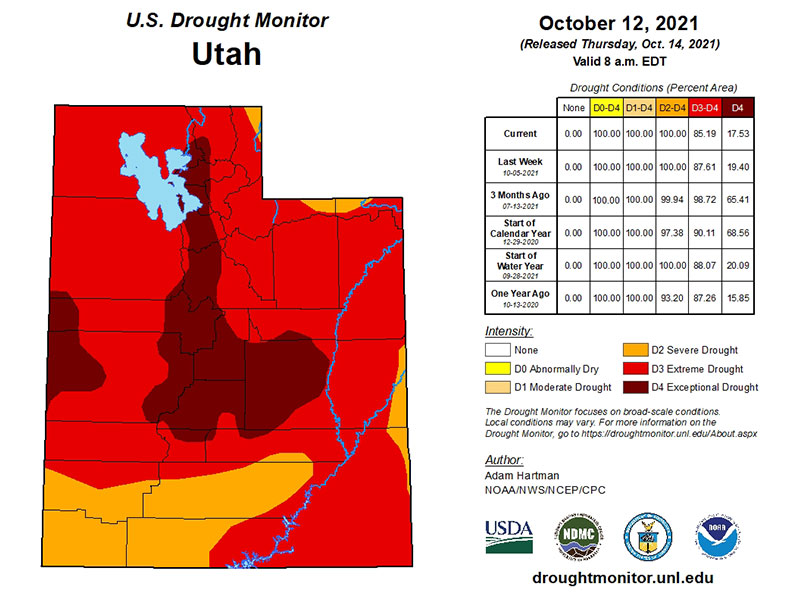

Even though we've had rain and snow in recent weeks, more than 85% of the state still falls into the two worst drought categories: extreme and exceptional drought.

Update on Utah's drought situation. Information is current as of Oct. 14, 2021.

Courtesy National Drought Mitigation Center, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Drought impacts all wildlife species. Some animals have adaptations that allow them to handle drought conditions better than others, but during extended periods without precipitation, all wildlife populations are affected.

A lot of people have asked me about how our deer herds are handling the current drought situation. The quick answer is that our herds are struggling, but a better answer delves into the following complex reasons:

- Quality and quantity of vegetation

- Age and sex of deer

- Severity of conditions

This is a more thorough look at the effects of drought on our deer populations — and the habitat they depend on — and some of the steps we're taking to try and help.

Quality and quantity of vegetation

Plants need water in order to grow, and deer need plants as a food source. When drought puts stress on plants, there's a negative ripple effect on deer and other wildlife that depend on high-quality vegetation in large quantities.

If there is insufficient moisture, plant growth is stunted and also lacks the nutrition that deer need for survival and reproduction. Without proper nutrition, deer will not gain the necessary fat reserves to make it through the winter. Malnourished deer are less likely to survive and successfully reproduce.

Drought has different impacts on plants and deer, depending on the time of year.

Spring/summer drought impacts

In the spring, plants begin to turn green and grow tender new shoots. This new growth is very palatable to deer and contains rich nutrients such as protein and calcium. The spring "green-up" of healthy plants is what deer need most after being in a nutritional deficit during the winter months.

Mule deer eat a lot of leafy, flowering plants (called forbs) in the spring and summer. These plants have exceptionally high nutritional value, but many of them — especially in southern Utah — have adapted to drought conditions. When there is insufficient moisture, these plants will not produce flowers and may go dormant.

Drought's resulting reduction in vegetation quality and quantity during the spring and summer months decreases the ability of mule deer to put on much-needed fat before winter arrives.

Fall/winter drought impacts

Shrubs like sagebrush and bitterbrush are a valuable part of mule deer diets year-round, but particularly in the fall and winter. Drought conditions can limit new growth on shrubs in the spring, which in turn limits food availability during the winter. Mule deer prefer to browse on the new growth because it is the most tender, nutritious part of the plant and is rich in protein.

Unfortunately, drought conditions also make the new growth on shrubs harden faster than usual, limiting a deer's ability to eat and digest it effectively. If shrub growth is insufficient or too tough to eat, that can be a problem for deer, who ideally need to build up their fat reserves during summer and fall. Having adequate body fat is one of the key factors determining whether mule deer survive the winter or not.

Age and sex of deer

A deer's age can make it more susceptible to the effects of drought. Fawns raised in drought conditions may not be able to put on sufficient fat reserves before their first winter arrives.

During drought conditions, fawns are born smaller and grow more slowly than during wetter periods. If fawns do not reach a sufficient size and weight prior to winter, they will not have enough energy reserves to make it through, especially if the winter is severe.

Drought also affects deer differently, depending on whether they are female or male.

How drought impacts does

For adult female deer (does), drought can lead to poor body condition and result in the following possible outcomes:

- Decreased adult survival

- Stillborn births

- Low birth weights and poor newborn fawn survival

- Inadequate milk supply to nourish a fawn

Sometimes, a doe will carry a fawn full-term and raise it, but the newborn fawn is much smaller than a fawn born in a non-drought year. Smaller, weaker fawns are less likely to survive their first winter, especially if conditions are harsh.

Milk production (lactation) is also very demanding on a doe's body. If drought affects a doe's milk supply, that can lead to decreased survival of newborn fawns during both the summer and winter months.

Drought can reduce deer population growth by impacting both survival and reproduction:

- Survival impacts: Adult doe survival averages around 85% in Utah, but even a small drought-induced decline in survival — even if it's only 5% — can have widespread impacts on overall population growth.

- Reproduction impacts: In non-drought years, twins are a normal occurrence for mule deer. If the does stop having twins, or even single fawns, it reduces the whole population.

Having fewer deer overall means there will be fewer bucks available to hunters, possibly for years to come.

How drought impacts bucks

Drought can affect antler growth for bucks. And although antlers are not necessarily needed for survival, they can improve the likelihood of winning mating battles and achieving reproductive success.

During drought years, bucks will not have surplus nutrition to grow antlers as large as they might in a non-drought year. They will still produce them — and they may be big — but perhaps not as big as they would grow during a year with good precipitation.

If a pregnant mule deer doe is in poor body condition, it will affect any fetuses she is carrying. They will not receive optimal nutrition and will likely be smaller at birth and throughout their lives. This is why bucks born to drought-affected does may have smaller antlers. With all of this in mind, don't be surprised if you see fewer bucks — and smaller bucks — during the fall hunt.

Severity of conditions

It almost goes without saying, but extreme weather at the wrong time can also have a negative effect on deer populations within an area or region.

I've traveled all over the state this year, and we didn't just have low water levels in our rivers and reservoirs: There are places that are bone dry. Some mountain streams and springs have dried up completely. When water sources start to disappear, that's definitely a concern for wildlife.

Extreme drought conditions also increase the likelihood of wildfires, which can damage watersheds and deer habitat. Fortunately, Utahns were careful this year, and although there were many human-caused fires, most were quickly extinguished.

Heavy late-winter storms, deep snow and extreme cold are also problematic for our deer herds. As the winter grinds on, deer use every last fat reserve to stay alive. If they have to move often to find food or cover — or to avoid people — that depletes their energy and reduces their likelihood of survival.

What we're doing to help

When it comes to drought, Mother Nature holds most of the answers — and recent precipitation looks promising. In the meantime, we've taken the following steps to try and help our deer herds:

- Restored more than 2.2 million acres of watersheds and wildlife habitat since 2006, as part of Utah's Watershed Restoration Initiative. We've reseeded wildfire-damaged areas with drought-resistant plants and planted vegetation that specifically benefits deer.

- Placed GPS tracking collars on thousands of deer as part of the Utah Wildlife Migration Initiative. Tracking these animals allows us to target placement for wildlife crossings and habitat projects in specific areas where they are most needed.

- Built and refilled water guzzlers in some of the state's driest areas to ensure that animals have water to drink.

- Made changes to certain activities (such as camping) on many wildlife management areas so they can provide good places to hunt and fish during the appropriate seasons and serve as critical habitats and rest areas for Utah's wildlife the rest of the year.

- Shared tips with the public for how to reduce conflicts with deer during the drought.

- Routinely monitored deer herds during the winter to ensure they're surviving deep snow and cold temperatures.

- Targeted predator control in areas where deer populations are struggling and being negatively impacted by predators.

- Reduced the number of hunting permits for the 2021 deer season.

Final thoughts

I grew up here in Utah and have spent most of my adult life working to study and manage our deer herds and to improve their habitats. I love to see fawns and does in the summer, and I love to hunt bucks in the fall.

Having healthy, thriving deer herds is a very personal issue for me. I'm grateful for every ounce of precipitation we receive and hope this drought will soon be far behind us. In the meantime, I'm committed to developing habitat improvements with my DWR colleagues, implementing survival/migration studies so we have the best data possible to inform our decisions, working with our many conservation partners and trying any other innovative solutions we can put in place to help our deer.