Tooth seeker

Why do we collect tooth samples from deer and elk, and what do we learn from them?

Heather Bernales

Biometrician

Salt Lake Office Wildlife Section

Have you ever wondered why the DWR requests that you submit a lower incisor — that's a front, middle tooth from the bottom jaw — if you successfully harvest an elk, mule deer, pronghorn, moose, mountain goat or bighorn sheep from a limited-entry or once-in-a-lifetime hunt?

The short answer is that biologists can determine the age of an animal, just from a tooth.

The longer answer? By looking at the tooth analysis data gathered from harvested male animals, we can more accurately and effectively manage healthy animal populations in Utah. For more than 20 years, we have been using tooth analysis as one of the most effective and hunter-friendly methods of determining the age of an animal. Since we've been doing this for so long, the accumulated age data helps us understand more about the composition of animal herds spread out over the landscape. We're the envy of many other wildlife agencies because this robust data set is available to guide our management.

The whole tooth and nothing but the tooth

When a hunter submits the requested tooth, we send it to Matson's Laboratory in Montana — one of the few (if not only) labs in the U.S. that does this type of wildlife teeth aging.

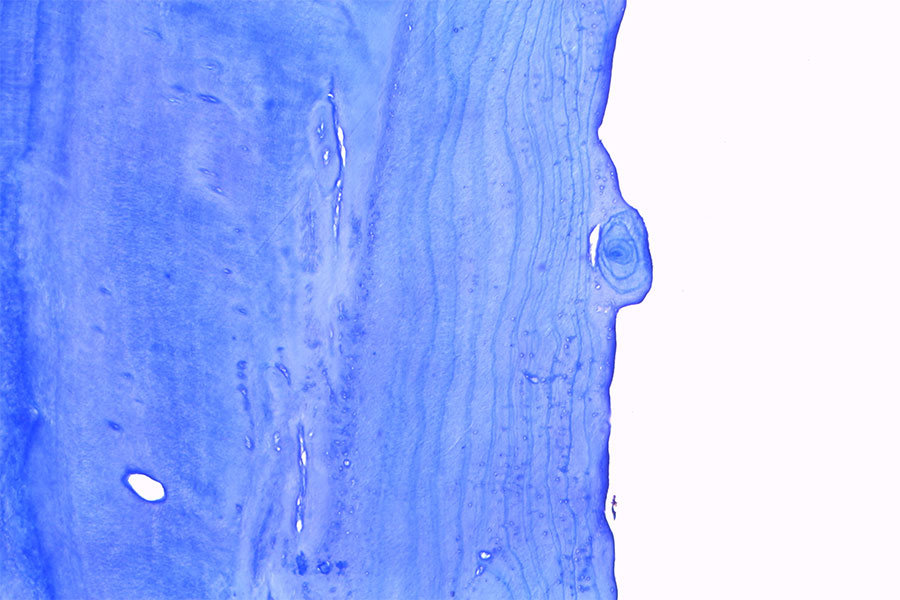

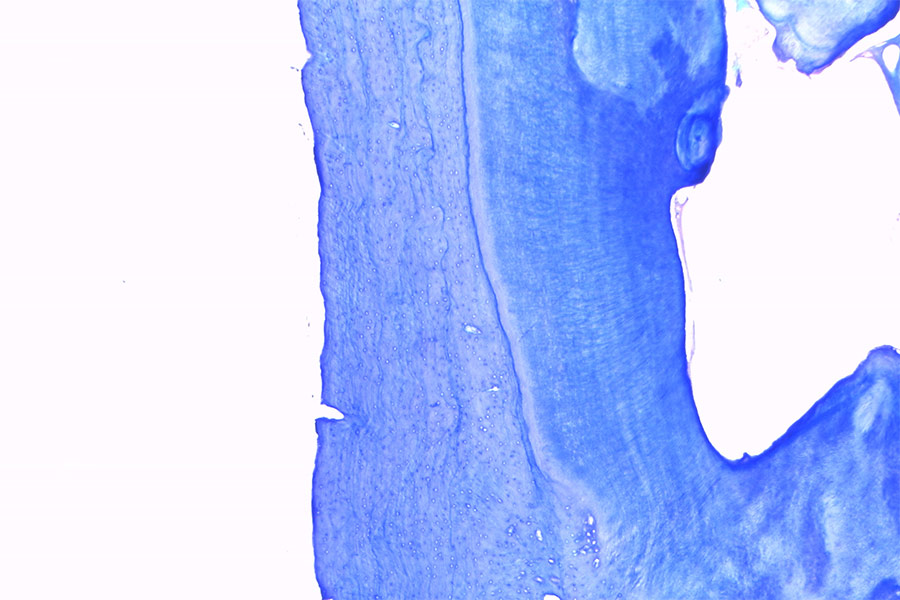

At the lab, the tooth is cut horizontally and a very thin cross-sectional slice is placed on a slide, then viewed through a microscope. The tooth cross section will show a bunch of dark circles or rings, like rings in the trunk of a tree. Each dark ring represents a period of nutritional stress corresponding to winter forage scarcity. Counting each "winter ring" gives us a count of how many years the animal has lived.

It's important to submit the correct tooth — for example, an incisor and not a molar — because the patterns of the tooth cross sections vary depending on tooth type, and it's harder to distinguish these rings in some kinds of teeth than others. Also, it is key that we collect the entire incisor — down to the root — without anything else attached (like pieces of the jaw bone or adjacent teeth). It is actually the tooth's root that is sliced and viewed, so if part of the root is broken when the tooth is removed, it becomes more difficult to age. Ideally, both lower incisors from an animal are sent in for analysis so that there's a backup if one is damaged or unusable.

Elk teeth are sent to the laboratory where a very thin cross section of the root is scanned to determine the age of the animal. The photo on the right shows the dark "winter rings" present in the tooth of an 11 year-old elk.

Slide photo credit: Matson's Lab

How to take a "good" tooth sample

If you draw a limited-entry or once-in-a-lifetime permit, you'll receive instructions with your permit about how and when to send in a tooth sample. Heather and Matson's Lab shared some tips for collecting the best samples:

- Teeth are most easily extracted from a freshly harvested animal, either in the field or as soon as you get home.

- Use a sharp knife to cut down through the gum tissue on both sides of the two lower incisors. Be very careful not to cut into the tooth root itself.

- Use the back of a knife to gently pry each tooth forward and out of the jaw.

- Don't scrape, bleach or boil the teeth or roots; very small pieces of attached bone or tissue are okay. Whole jaws are not accepted.

- Allow teeth to dry completely in open air for at least one week before shipping (the U.S. Postal Service won't deliver samples with strong smells).

- Make sure to keep the teeth away from pets — especially dogs, who find them irresistible and will eat them!

- Do not place teeth in plastic bags or plastic wrap at any point.

- Store and ship using the paper envelope and padded mailer provided by the DWR, and remember to fill out all applicable information fields on the collection envelope.

- To find out the age results: After March, log in to the DWR hunt return card portal. Select the “My Harvest Survey” tab, then select “View.” If an age was determined, it will be noted at the bottom of your previously-submitted harvest survey.

Remember: Sending in a tooth sample doesn't take the place of submitting your mandatory harvest survey.

Long in the tooth: Why is determining age so important for management?

Many of our limited-entry and once-in-a-lifetime big game species hunts are managed for an "age objective." This means that we determine how many buck and bull permits to issue each year based upon the age data collected from hunter-harvested animals the previous three years, while still maintaining a higher "quality" hunt in these specific units.

The higher the age-class objective, the greater likelihood of a hunter harvesting a larger, older animal. Lower age objectives result in a larger overall number of hunters with permits having an opportunity to successfully harvest any legal buck or bull. These management techniques are sometimes viewed as a "quality vs. opportunity" approach to hunting.

For example, if a management unit has an elk age objective of 4.5 to 5.5 years, and the average age of harvested bull elk from that hunt during the last three years was 6.2 years old, our biologists would recommend issuing more bull elk permits the following year. This would hopefully result in the reduction of those older-aged bulls until the average-age bull taken by hunters drops down to within the desired range.

Tooth and consequences

Our recent Utah Pronghorn Statewide Management Plan is an interesting case study of the usefulness of collecting this type of data.

We developed a study to observe how pronghorn buck size correlated with age. In partnership with Brigham Young University, we collected horn length and circumference measurements and aged the teeth from harvested buck pronghorn for several years. Surprisingly, we found that buck pronghorn reached their peak horn size at a younger age than expected, typically by 3 years of age.

In other words, the size and antler quality of a 3-year-old buck pronghorn were basically no different than those of a 4-year-old, 5-year-old or even 8-year-old animal. The average ages of harvested bucks in most management units exceeded this desired peak-size age. This meant that we could issue more buck pronghorn permits without losing the quality our hunters expect from a limited-entry hunt.

To learn more about the science behind tooth aging and how it helps us determine management policies, check out our recent interview on the DWR "Wild" podcast!

DWR "Wild" Podcast

In this episode, DWR Biometrician Heather Bernales explains why the Division requests that hunters send in teeth sometimes from animals they have harvested. She talks about what we do with the teeth, what we learn, and how that helps shape certain wildlife management plans in Utah.