Wildlife-friendly fences

Consider wildlife needs and movement when designing your backyard fence or ranch fence in the wildland-urban interface

Melissa Early

DWR Northern Region Impact Analysis Biologist & Assistant Habitat Manager

Jen O'Leary

DWR Northern Region Wildlife Technician

The American West is covered with networks of fences that have been installed for a variety of purposes: property boundary separation, livestock management, trespass prevention, or keeping children and backyard pets safe. However, many of our fenced-off areas are also important for wildlife habitat and movement across the landscape. And as our cities and suburbs expand into previously undeveloped areas, our structures, roads and other barriers — including fences — can act as an unintentional but often fatal restriction for many wildlife species.

Fortunately, there are many fencing options available to meet the needs of landowners while also keeping wildlife safety, health and movement in mind.

When wildlife movement and fencing are at odds

Much of Utah's public and private lands have been used historically as wildlife migration corridors; routes that wildlife follow between summer and winter habitat that are based on learned patterns. Migration corridors are areas of land that possess resources for wildlife such as food, water and shelter. (Learn more about Utah's Wildlife Migration Initiative.) These habitats are often hemmed in by miles of fencing that wildlife navigate through or perish on.

Fences not designed with wildlife in mind can have negative effects on wildlife populations.

Examples of historical barbed wire fencing impacting wildlife. These photos were taken at the Henefer-Echo Wildlife Management Area, where the DWR is inventorying fences to bring them up to wildlife-friendly standards and improve wildlife movement.

Large mammals

Some of the impacts of fencing choices are observable, such as a deer impaled and hanging from a wrought iron fence in a backyard garden. Or the suffering and eventual death of a deer that gets a hoof caught in a loose top wire of a barbed-wire fence. Even when animals free themselves from fences, there's an increased risk of dying from infected cuts and wounds they incidentally receive while struggling to get out. Or, young fawns can perish from starvation when they can't follow their mother to a seasonal range due to a fence barrier.

Even when animals free themselves from fences, there are still risks and impacts.

Other impacts are less visible, such as reducing gene flow and genetic diversity in fence-restricted wildlife populations, making them more vulnerable to diseases. And wildlife risks are often dependent on the fence condition; damaged and dilapidated fences can tangle and entrap many wildlife species at all stages of life.

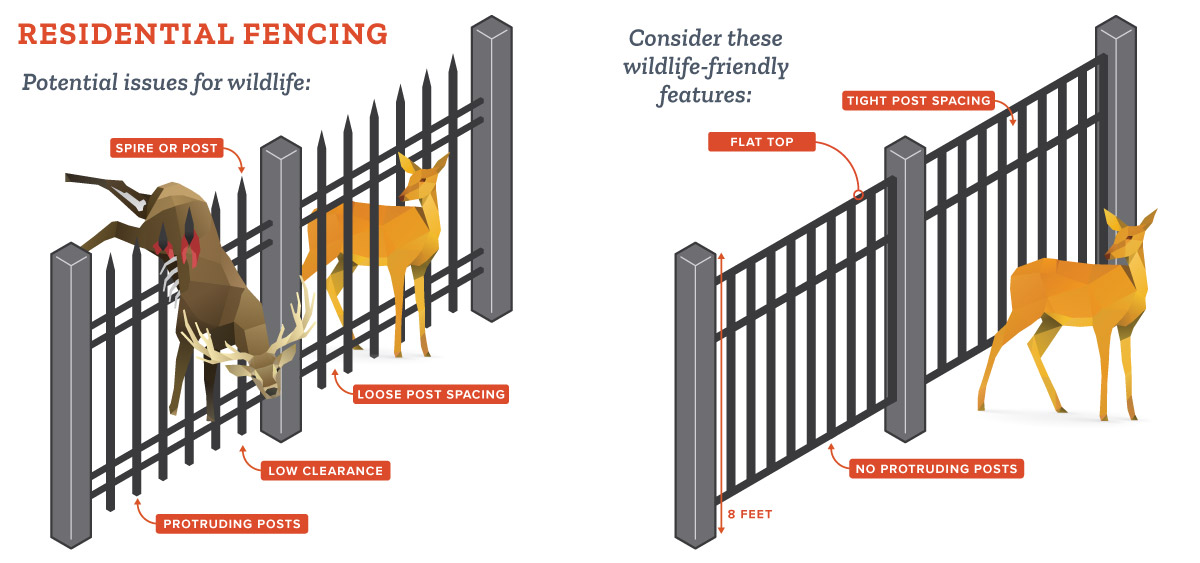

Decorative yard fences can be a danger to wildlife

Wrought iron decorative fences with pointed top posts are among the most deadly types of fences encountered by deer and elk in the wildland-urban interface and backyards:

DWR wildlife technicians are often called to remove dead or dying animals impaled on backyard fences, such as this mule deer in a northern Utah neighborhood. Note: a portion of this photo has been obscured.

- Every year, DWR staff respond to many residential neighborhood encounters of deer or elk impaled in the abdomen or caught by a back leg, and then suffering and dying. No wildlife survives impalement.

- Fawns may become trapped between the spaces of wrought iron fences, preventing them from moving forward or backward. While caught in the fence, fawns attempt to wiggle, crawl or climb out. The friction from the fence rubs the hair off and lacerates the delicate skin on their haunches.

- If they escape, they have minor injuries at best. Unfortunately, the most common outcomes are dislocated hips (for fawns), bacterial infection, or blowflies laying eggs in the exposed wounds and becoming infested with maggots. All of these are fatal to the animal.

When responding to a wildlife conflict, DWR personnel must evaluate if the animal has a chance to survive or not. Unfortunately, most animals caught in fences must be euthanized. When possible, an attempt to have the animal carcass donated is made if the meat is in good condition. If the animal is not in a condition to be donated, it is removed, and the carcass disposed of in the county landfill.

Birds

Fences with low-visibility metal wires can have negative impacts on bird species if they collide with the wire. Common fence collision injuries in birds are broken wings and ruptured crops. These types of injuries prevent birds from escaping from predators or capturing prey, which shortens their lifespans. Fences can restrict migration, daily movements and cause deadly tangles.

Options for wildlife-friendly fencing

A long-eared owl died after colliding with this range fence in western Utah. Creating a visual cue on the fence, such as fence markers or flagging, may have prevented this entanglement and death.

Fortunately, fences can be designed to encourage historical migration patterns and wildlife movement on both a large and small scale. Whether on an expansive ranch or in an urban backyard, adaptive fencing can keep wildlife safe and meet the goals of landowners.

Wildlife-friendly fence design can make a significant positive difference on the landscape.

Residential fences in the wildland-urban interface

While the best fence for wildlife is no fence at all, fences to delineate property lines, discourage trespassing or maintain privacy are often a necessity. Keep wildlife movement and access to food and water in mind when selecting your fence design and materials.

Some creative fencing solutions to consider:

- A line of trees, shrubs or other vegetation can be used to mark a boundary. In addition to creating a living screen for privacy, this choice can provide additional food and cover for wildlife.

- Mark property boundaries with signs, flexible fiberglass or plastic boundary posts, or fence posts spaced at intervals without crosswires.

- If you only fence the portions of your property that you need to protect — for example, just a play yard or garden, instead of the entire property line — you'll be saving time, money and wildlife.

- To prevent access by vehicles, consider using bollards — short stout barrier posts — instead of fences. They can define a driveway or parking area, or edge a lawn or field.

If you are worried about deer or elk damaging your garden vegetables, fruit trees or other plants in your yard, an exclusion fence prevents wildlife from the area by preventing entry:

- An eight-foot-tall fence is typically an effective barrier. This height discourages elk and deer from jumping over the fence, and minimizes the risk of death or injury on the fence itself.

- Make the top of the fence highly visible with flagging, white tape or wire, or a rail.

- Note: Check your local ordinances for fence height restrictions.

- Visit Wild Aware Utah for more information about deer-proofing your yard.

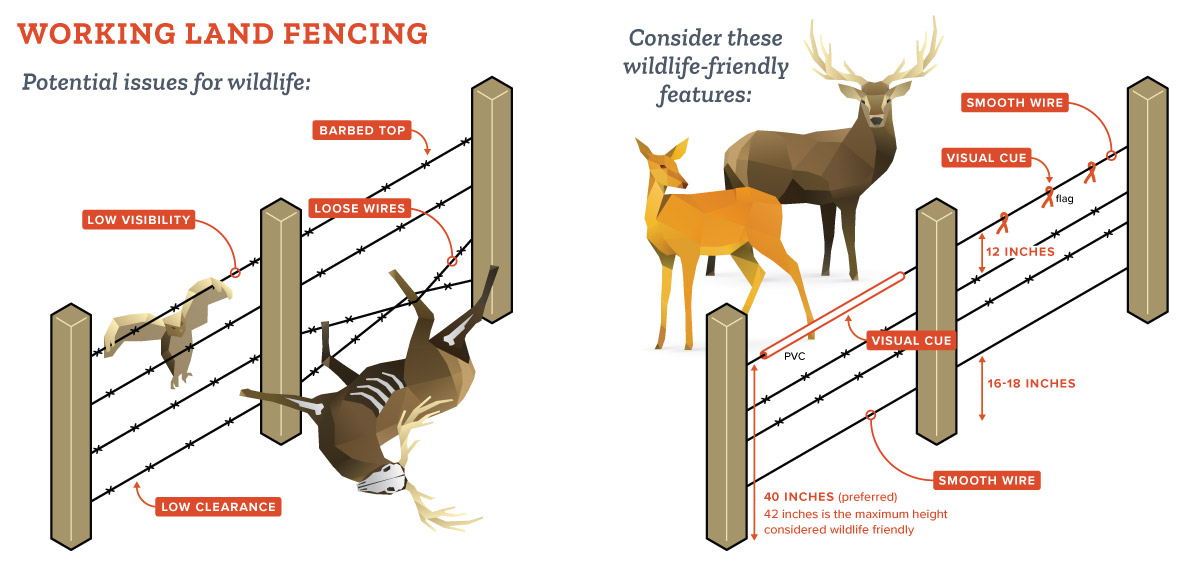

Working land fences

To keep livestock within a controlled area — and have fewer wildlife conflicts, damage and injuries — there are important strategies to consider, such as the height of the fence and materials used.

Studies have shown that the following fencing strategies adequately control livestock while also aiding wildlife movement:

- Allowing a 16-inch bottom wire gap from the ground allows fawns to crawl under a fence.

- Placing a taut, smooth top wire at a maximum of 42 inches (or more preferable, 38–40 inches) height allows wildlife to jump over the top of a fence with fewer injuries and less risk of hoof or leg entanglement.

- Allowing for a 12-inch gap between the top and second wire gives enough spacing to minimize the two wires tangling a hoof or leg.

- More detailed wildlife-friendly fence specifications for working lands are described in this Natural Resources Conservation Service technical note.

- To decrease bird collisions, place high visibility fence markers, flagging or a smooth PVC covered top rail on the fence.

- Fence markers can reduce collisions for sage-grouse by over 80% and are a simple yet effective tool.

Fence projects in Utah: enhancing wildlife movement

Collaborative efforts are underway in Utah to map fence conditions on public lands, and improve fence conditions to enhance safe wildlife movement. Along with the Bureau of Land Management, Sageland Collaborative, Wildlands Network and a wide-ranging group of stakeholders, we are embarking on a new fence mapping initiative.

With our robust group of community scientists, we are inventorying fence conditions and wildlife movement barriers beginning with a survey of public lands managed by the BLM. This project will provide land managers with a wealth of information to pair with GPS tracking technology. For example, we'll be able to compare wildlife movement behaviors near fences and evaluate the response of migratory wildlife populations across seasonal ranges. High-priority fences — especially within a migration corridor — may be targeted for removal or modification as needed.

Thoughtful fencing choices helps wildlife and people

Some foresight and planning can reduce wildlife conflicts before they result in death or injury. If your homeowners association requires decorative fencing, this is a great opportunity to lead by example. Perhaps you can be your area's wildlife champion to educate your neighbors and the HOA about fence options that are both attractive and friendly to wildlife.

Learn more

There are many great resources available to learn more about wildlife-friendly fencing options for residential and working lands:

- Fencing with Wildlife in Mind

- A Landowner's Guide to Wildlife-Friendly Fencing

- NRCS Technical Notes: Improving Fence Passage for Migratory Big Game

- Fence Markers to Prevent Sage Grouse Collisions

- Developing with Wildlife in Mind

- Guidebook to Wildlife-Friendly Fencing

- Absaroka Fence Initiative

- Wild Aware Utah