The not-so-simple definition of species

How geologic history and new genetic findings inform the identification of bluehead and green suckers in Utah

Randy Oplinger

DWR Assistant Aquatic Section Chief

What is a species? It seems like a straightforward question, right?

For example, we easily recognize that cutthroat trout and great white sharks are distinct species. Both are fish, but the two species look and act differently. One lives in freshwater and primarily eats insects, while the other lives in saltwater and mostly eats other fish and mammals.

A Bonneville cutthroat trout from the Weber River, shown here, is easily distinguishable from...

...a great white shark, like this one from the Pacific Ocean.

Unfortunately, defining what makes a group of animals a distinct species is actually far more complicated than it would appear on the outside.

Even if you're not a biologist, you may have learned about how scientists name and order the natural world in categories from very general to very specific: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus and species. But taxonomy — the science of classifying organisms into groups by relatedness — is an ever-changing field. It turns out that we are constantly gaining more knowledge about the relatedness of different species and we are even expanding the types of information we use to determine relatedness. Sometimes, new information requires us to reconsider what we know about species.

This means as fisheries biologists, we have to be on our toes and adapt how we manage fishes as the taxonomy of species changes.

So, how do we define a species?

Complicating matters, there are many ways to define what qualifies as a species. The typical textbook answer is that a species is a group of organisms that can reproduce with one another and produce fertile offspring. For example, striped bass are a species because striped bass can reproduce with other striped bass and their offspring are able to reproduce more striped bass. Striped bass and white bass are considered different species because if they do cross, their offspring (called wiper or hybrid striped bass) are not able to reproduce.

Another common definition of species is a population whose members breed mostly among themselves, making the group genetically distinct from other species. This definition gives us some insight into how different species are created over time even if they descended from a common ancestor. This often happens when a population is isolated because there is some kind of physical barrier (like a mountain range or a vast desert) that prevents one population from interacting with another. As a result, geologic history can have a big and lasting impact on the range of a species.

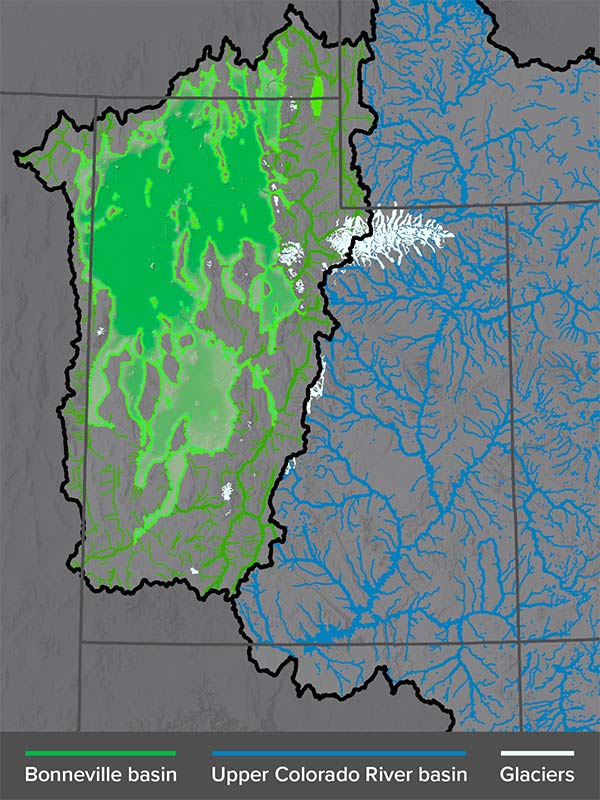

In the case of Utah, the state is largely broken into two major basins, influenced by the region's geologic history and the barrier of the Wasatch Mountains. To the west is the Bonneville basin — defined by historic Lake Bonneville and current-day Great Salt Lake — and the Colorado River basin that extends over most of eastern Utah (along with large portions of Wyoming, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico).

This geological divide often creates a west/east split in species in Utah. For example, species like least chub and leatherside chub are only found in western Utah because mountains prevent them from moving to the eastern part of the state. Similarly, Colorado River fishes like the Colorado pikeminnow and razorback sucker are restricted to the eastern half of the state because barriers prevent them from moving west.

Introducing: green suckers!

Historically, scientists grouped species together based on external appearance and internal anatomy. More recently, discoveries about genetic information have provided additional insights about the relatedness of different species.

As an example, genetic research has changed how we look at the taxonomy and distribution of sucker species in Utah. A recent study had surprising results. What we used to consider a single species, bluehead sucker, is actually two species: bluehead sucker and a new species that is called the green sucker.

Some interesting things we've recently learned about bluehead and green suckers:

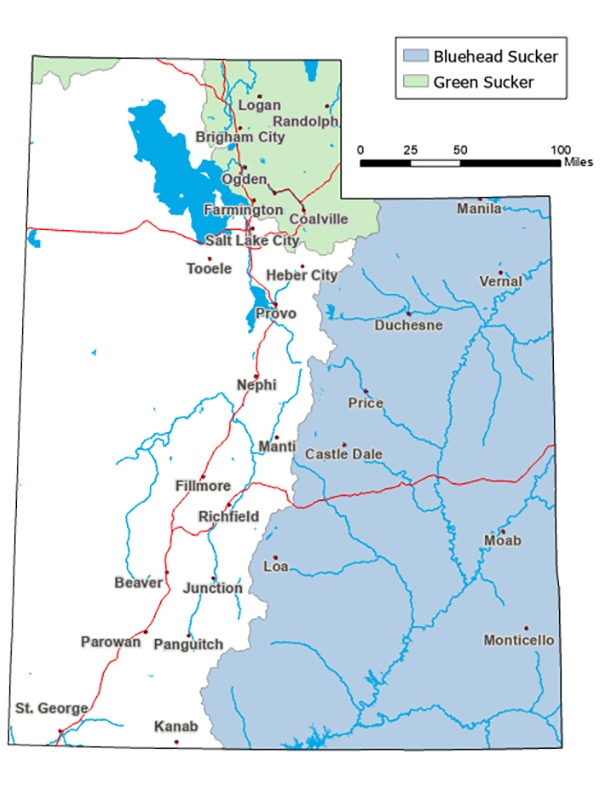

- The split between bluehead and green suckers occurs along geographic boundaries. All bluehead suckers found in the Colorado River basin are still considered bluehead suckers. However, fish that were formerly considered bluehead suckers that are found in the Weber River, Bear River and Raft River drainages are now considered green suckers.

- It's almost impossible to visually distinguish between bluehead and green suckers. But the genetic (DNA) differences confirm they are two distinct species.

- Bluehead sucker was formerly in the genus Catostomus, and we used to think that many sucker species were closely related enough to be included in that genus. However, we now know that there is a group of 11 sucker species that are more closely related to one another that have now been broken into a separate genus, Pantosteus. Among the 11 Pantosteus species, four are native to Utah: bluehead, green, mountain and desert suckers.

Managing for the future

Bluehead suckers have long been considered a species of greatest conservation need in Utah. We have been working to strengthen our populations through various conservation and habitat improvement projects. With the taxonomic change dividing bluehead and green suckers into two species, that means we have even smaller bluehead sucker populations than we originally recognized.

This means that agencies like the DWR do additional work to help protect these species from becoming threatened or endangered. Some examples:

- After observing a decline in green sucker numbers in the Weber River, we established a green sucker broodstock at our Logan Fish Hatchery. Eggs from this broodstock are being raised in the hatchery and stocked back into the Weber River to help boost the population.

- We are working with research partners to figure out why the Weber River green sucker population is declining, and we hope this research may uncover additional management actions we can take to help the green sucker populations in the river.

- Outside the Weber River, we are modifying water diversion structures so they can be passed by bluehead and green suckers (and other aquatic species). We are also screening diversion structures so fish do not get caught in ditches and canals.

- Utah's Species Protection Account funds various habitat improvement projects that are currently underway and will benefit bluehead and green suckers.

No matter what the future holds for fish taxonomy, our biologists will keep on top of all scientific and technological advances, and we will continue to adapt the management of fishes in Utah as new information comes forward. The DWR is committed to protecting native fishes, supporting statewide conservation needs and keeping the interests of our anglers at the forefront of fish management.

Green suckers, from the hatchery to the wild.

Learn more

- WILD podcast, Episode 48: Recovery programs

- WILD podcast, Episode 43: Helping endangered species

- DWR blog, Forward-thinking fisheries