Becoming a hunter

DWR's social media coordinator finally decided to pull the trigger

By Crystal Ross

DWR social media coordinator

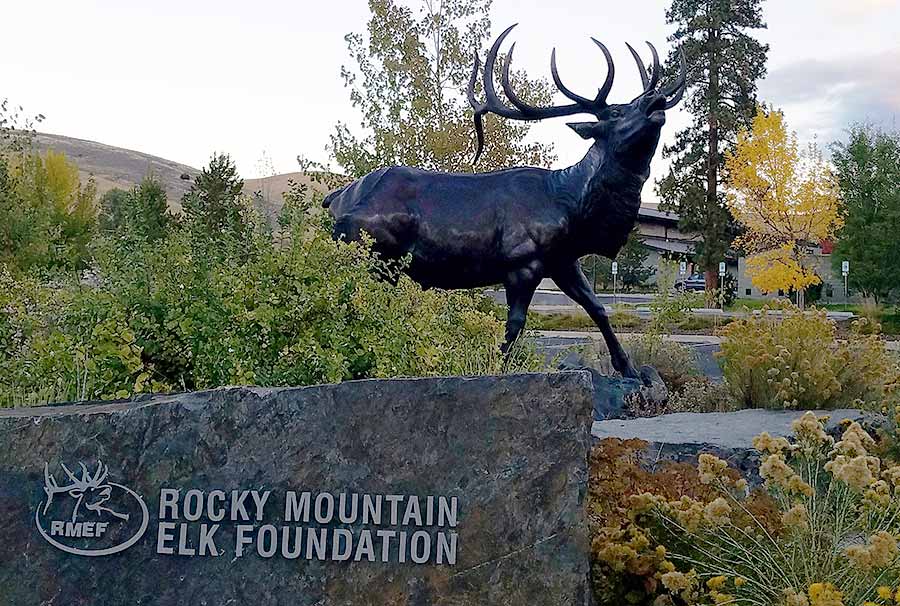

The CLFT workshop Crystal attended was held at the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation headquarters in Montana.

There I was, stomping through a field in the middle of Montana, shooting at pheasants. My first hunt was happening — and it was with a group of skilled hunters and professional guides. I felt confident, and surprisingly excited, about shouldering a shotgun and pulling the trigger.

Real talk: I never expected to become a hunter. There was a short stint, not more than a decade ago, that I lived a vegan lifestyle. (I just heard you gasp.) At the same time, I became pretty heavily involved in domestic animal rescue, too. So I mean it when I say, I really never expected to head for the hills, intent on killing an animal.

So how did I get from there to a Montana pheasant hunt? It probably seems like a drastic move. When a strong pregnancy craving for chicken strips and egg salad sandwiches ended the vegan stint, I started looking into ways to obtain healthy, antibiotic-free and ethically sourced meat.

Around the same time, I began working at the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. Part of my job was to share stories of the Division's wildlife-management efforts with the public, so I quickly learned about wildlife conservation and the role hunting and fishing plays in maintaining healthy wildlife populations (species that are hunted and fished, as well as those that are not).

Discussions with biologists opened my eyes to the level of passion that goes into species management in this state. The people who work here really care. This isn't just a job for them — it's a lifestyle. Many of them strived for a career with the Division because they hunt, and they wanted a chance at hands-on conservation.

I vividly remember a lunchtime conversation with a biologist/hunter, sharing the story of his latest harvest. "Killing an animal is brutal. It's never easy. It's the taking of a life." He talked about how he honors the lives of each of the animals he takes — how he silently thanks them for providing healthy meat for his kids. It's a whirlwind of complex feelings from excitement at success, to sadness of death. He said that for the thoughtful hunter, it's a rather sorrowful process.

Hearing him describe hunting that way intrigued me. It sounded emotional, maybe even spiritual. It seemed like such a gratifying experience. But I didn't know how to hunt. And I wasn't familiar with firearms. I shelved the idea of being a hunter myself.

A little later, the opportunity to attend the Conservation Leaders for Tomorrow (CLFT) program in Missoula, Montana presented itself. This workshop is designed for natural resource professionals — especially those who do not have a hunting background — to gain an understanding of the diverse values and critical roles of hunting and its impact on conservation. The Division encourages its employees who haven't hunted to attend.

I thought I already had a decent grasp of these concepts, but it turns out, I'd barely scratched the surface. I attended the workshop thinking it would just be the next step in my professional development, but it actually played a significant role in my personal life, too.

The week of the workshop consisted of field exercises, lively roundtable discussions, all kinds of demos, technical presentations, shooting practice and a Hunter Education course. And the final day of the workshop featured an optional guided pheasant hunt.

All instructors are experienced hunters and include wildlife conservation professionals and university professors. The attendees in my group included a variety of natural resource professionals, from attorneys and office admins to biologists and graphic designers.

It's easy for hunters to grasp how hunting is conservation, but for those outside of hunting, it can be confusing. Many don't know that hunters pay for habitat, research and wildlife law enforcement. Learning the history of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation and going over the logistics of the Pittman-Robertson Act during the workshop really helped clear up this concept for me.

I didn't know that back in the 1930s, hunters requested an 11-percent tax on guns, ammo, bows and arrows to help fund conservation — that they voluntarily imposed this tax on themselves, and it generates $700 million annually. That money is critical in conserving many species, including countless species that aren't hunted at all.

Regulated, responsible hunting is the driving force that maintains abundant wildlife. And I made the decision: I want to be part of that. But I don't just want to tell the stories. I want to make my own.

The grand finale of the CLFT workshop was the hunt, and I decided to partake. I couldn't get enough of watching the dogs work. And having never been to Montana, I was in awe of the natural beauty in every direction. Anticipation, laughter and our mentors' past hunt stories filled the fields while we searched for birds. Far away from home — and even further from my comfort zone — I was content, unplugged and in the midst of a total psychological cleanse. I understand, completely, why hunters view hunting as a cultural value and tradition to pass to their kids. It's much more than a hobby.

Still a little nervous handling my firearm, I missed when I took a shot at a rooster that flew into my zone of fire. But that didn't matter. I knew that once I was back home and able to put in some practice at the shooting range, I'd try my hand at hunting again. Others in my group harvested some pheasants that day, and they beamed with pride. I wasn't the only one who'd evolved into a hunter that week.

My husband and two kids (all fervent carnivores) support me and my newfound interest in harvesting my own meat. Thanks to gracious and patient friends and coworkers, I have the guidance I need to become a successful hunter in Utah. The tricky part for me is actually shooting something. That occasion will likely warrant its own blog post at a later date.